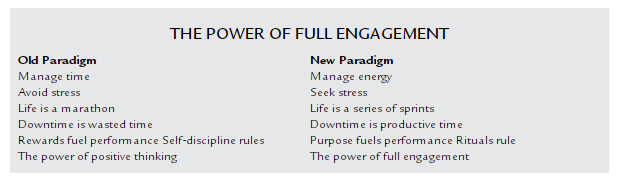

Think of how we make decisions in organizations — we often do what standard decision theory would ask of us.

We create a powerpoint that identifies the future desired state, identify what might happen, attach weighted probabilities to said outcomes, and make a choice. Perfectly rational. Right?

One of the problems with this approach is the risk charts and matrices that accompany this analysis. In my experience these charts are rarely discussed in detail and become more about checking the ‘I thought about risk’ box than anything else. We conveniently pin things into categories of low, medium, or high risk with a corresponding “impact” scale.

What gets most of the attention is high-risk, high-impact. Perhaps deservedly so. But you have to ask yourself how did we arrive at these arbitrary scales? Is one person’s look at risk the same as someone else’s? Are there hidden incentives to nudge risk one way or another? What biases come into play?

Often we can’t even identify everything. Rarely do people ever go back and look at what happened and how accurate those “risk” tables were. From the ones I’ve seen, the “low risk” stuff happens a lot more often than people imagined. And a lot of things happen that never even made the chart in the first place.

On the occasion when people do go back, and I’ve seen this firsthand, hindsight bias creeps in. “Oh, we discussed that but it didn’t make it in the document. But we knew about it.” Yes, of course you did.

Ignorant and unknowing.

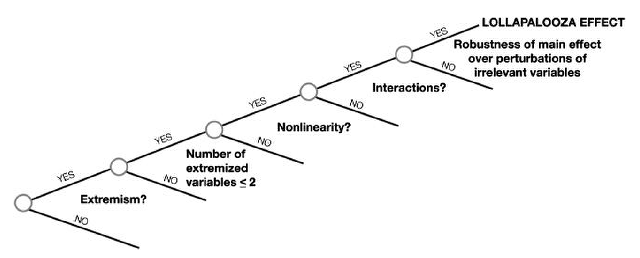

We’re largely ignorant, that is, we operate in a state of the world where some possible outcomes are unknown. However, we’ve prepared for a world where outcomes and probabilities can be estimated. There is a mis-match between our training and reality. You can’t even hope to accurately estimate probabilities if the range of outcomes is unknown.

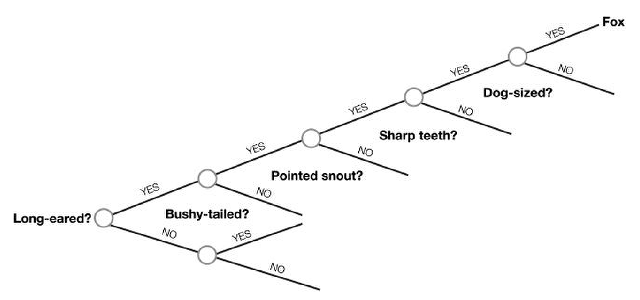

There are two types of ignorance.

The first category is when we do not know we are ignorant. This is primary ignorance. The second category is when we recognize our ignorance. This is called recognized ignorance.

[The Empty Suit/Fragilista] defaults to thinking that what he doesn’t see is not there, or what he does not understand does not exist. At the core, he tends to mistake the unknown for the nonexistent.

That my friends is primary ignorance. And it’s not limited to empty suits and fragilistas. Consider Anna Karenina:

Primary ignorance ruins the life of one of fiction’s most famous characters,

Anna Karenina. Readers of Anna Karenina (1877/2004) know that, in this novel, a train bookends bad news. Anna alights from one train as the novel begins and throws herself under another one as it ends. As she enters the glittering world of pre-Revolutionary Saint Petersburg, Anna catches the eye of the aristocratic bachelor Count Vronsky and quickly falls under his spell. But there is a problem: she is married to the rising politician Karenin, the two have a son Seryozha, and society will not take kindly to the conspicuous adultery of a prominent citizen. Indulging in an extra-marital affair, especially when one’s husband is a respected member of society, promotes the likelihood of unpleasant (events). But her passion for Vronsky dulls Anna’s capacities for self-awareness. She becomes pregnant out of wedlock, a disastrous condition for a woman in nineteenth-century Russia. Anna consistently displays an unfortunate propensity to take action without recognizing that a terrible consequential outcome is possible. That is, she operates in primary ignorance.

Anna demonstrates all the characteristics of primary ignorance. She fails to consider all the possible scenarios that will occur from her impulsive decision making. She risks her marriage with Karenin, a kind if undemonstrative husband, who is willing to forgive and even offers to raise her illegitimate child as his own. Leaving Seryozha with Karenin, she and Vronsky escape to Italy and then to his Russian country estate. Ultimately, she finds that while Vronsky continues to be accepted socially, living his life exactly as he pleases, the door of society slams shut in her face. No one will associate with her and she is insulted as an adulterer wherever she goes. It is only when she is completely isolated socially and cut off from her beloved son that Anna recognizes the dangers of primary ignorance: she risked her family and her reputation for too little. … She realizes she was ignorant of the possible outcomes that jumping headlong into an illicit relationship would bring.

Ignorance, primary or recognized, is only important if the expected consequences are significant. Otherwise we can be ignorant without consequence.

While human irrationality factors into all decisions, it hits us most when we are unknowingly ignorant. Rational decision making becomes harder as we move along the continuum: outcomes are known —> risk —> uncertainty/ignorance.

If we can not consider all possible outcomes, preventing failure becomes nearly impossible. Further complicating matters, situations of ignorance often take years to play out. Joy and Zeckhauser write:

One could argue … that a rational decision maker should always consider the possibility of ignorance, thus ruling out primary ignorance. But that is a level of rationality that very few achieve.

If we could do this we’d always be in the space of recognized ignorance, better, at least, than primary ignorance.

Literature

“Fortunately,” write Joy and Zeckhauser, “there is a group of highly perceptive chroniclers of human decision-making who observe individuals and follow their paths, often over years or decades. They are the individuals who write fiction: plays, novels, and short stories describing imagined events and people (or fictional characters.)”

Joy and Zeckhouser argue these works have “deep insights” into the way we approach decisions, “both great and small.”

In the

Poetics, a classical treatise on the principles of literary theory, Aristotle argues that art imitates life. We refer here to Aristotle’s ideas of

mimesis, or imitation. Aristotle claims one of art’s functions is the representation of reality. “Art” here includes creative products of the human imagination and, therefore, any work of fiction. Indeed, a crevice, not a canyon, separates faction and fiction.

For centuries, authors have attempted to depict situations of ignorance. In Greek literature, Sophocle’s King Oedipus and Creon, and Homer’s Odysseus all seek forecasting skills of the blind prophet Tiresias who is doomed by Zeus to “speak the truth no man may believe.”

For its status as one of literature’s most enduring love stories, Jane Austen’s

Pride and Prejudice begins rather unpromisingly: the hero and the heroine cannot stand each another. The arrogant Mr. Darcy claims Elizabeth Bennet is “not handsome enough to tempt

me”; Elizabeth offers the equally withering riposte that she “may safely promise …

never to dance with him.” Were we to encounter them after these early skirmishes, we (like Elizabeth and Darcy themselves) would be ignorant of the possibility of an ultimate romance.

In Gustave Flaubert’s

Madame Bovary (1856/2004), Charles Bovary is a stolid rural doctor who is ignorant of the true character of the woman he is marrying. Dazzled by her youth and beauty, he ends up with an adulterous wife who plunges him into debt. His wife Emma, the titular “Madame Bovary,” is equally ignorant of the true character of her husband. Her head filled with romantic fantasies, she yearns for a sophisticated partner and the glamor of city life, but finds herself trapped in a somnolent marriage with a rustic man.

K., the land surveyor and protagonist of Franz Kafka’s

The Castle, attempts, repeatedly and unsuccessfully, to gain access to the mysterious authorities of a castle but is frustrated by an authoritarian bureaucracy and by ambiguous responses that defy rational interpretation. He begins and ends the novel (as does the reader) in ignorance.

Joy and Zeckhouser use stories to study ignorance, which makes sense.

Stories offer “simulations of the social world,” according to Psychologists Raymond Mar and Keith Oatley, through abstraction, simplification, and compression. Stories afford us a kind of flight simulator. We can test run new things and observe and learn, with little economic or social cost. Joy and Zeckhouser believe “that characters in great works of literature reproduce the behavioral propensities of real-life individuals.”

While we’ll likely never uncover situations as fascinating as we find in stories, this doesn’t mean they are not a useful tool for learning about choice and consequence.

“In a sense,” Joy and Zeckhauser write, “this is why great literature will never get dated: these stories observe the details of human behavior, and present such behavior awash with all the anguish and the splendor that is the lot of the human predicament.

Characters in a fictitious world do exactly what our intelligence allows us to do in the real world. We watch what happens to them and mentally take notes on the outcomes of the strategies and tactics they use in pursuing their goals.

If we assume we live in a world where we are, to some extent, ignorant then the best course is “thoughtful action or prudent information gathering.” Yet, when you look at the stories, “we frequently act in ways that violate such advice.”

So reading fiction can help us adapt and deal with the world of uncertainty.

References: Ignorance: Lessons from the Laboratory of Literature (Joy and Zeckhauser).