We live in a digital time which Schwartz and Loehr capture so eloquently:

We live in digital time. Our rhythms are rushed, rapid fire and relentless, our days carved up into bits and bytes. We celebrate breadth rather than depth, quick reaction more than considered reflection. We skim across the surface, alighting for brief moments at dozens of destinations but rarely remaining for long at any one. We race through our lives without pausing to consider who we really want to be or where we really want to go. We’re wired up but we’re melting down.

Most of us are just trying to do the best that we can. When demand exceeds our capacity, we begin to make expedient choices that get us through our days and nights, but take a toll over time. We survive on too little sleep, wolf down fast foods on the run, fuel up with coffee and cool down with alcohol and sleeping pills. Faced with relentless demands at work, we become short-tempered and easily distracted. We return home from long days at work feeling exhausted and often experience our families not as a source of joy and renewal, but as one more demand in an already overburdened life.

We walk around with day planners and to-do lists, Palm Pilots and BlackBerries, instant pagers and pop-up reminders on our computers— all designed to help us manage our time better. We take pride in our ability to multitask, and we wear our willingness to put in long hours as a badge of honor. The term 24/ 7 describes a world in which work never ends.

“Energy, not time, is the fundamental currency of high performance.”

“Every one of our thoughts, emotions and behaviors has an energy consequence,” they write. “The ultimate measure of our lives is not how much time we spend on the planet, but rather how much energy we invest in the time that we have.”

There are undeniably bad bosses, toxic work environments, difficult relationships and real life crises. Nonetheless, we have far more control over our energy than we ordinarily realize. The number of hours in a day is fixed, but the quantity and quality of energy available to us is not. It is our most precious resource. The more we take responsibility for the energy we bring to the world, the more empowered and productive we become. The more we blame others or external circumstances, the more negative and compromised our energy is likely to be.

To be fully engaged, we need to be fully present. To be fully present we must be “physically energized, emotionally connected, mentally focused and spiritually aligned with a purpose beyond our own immediate self-interest.”

Conventional wisdom holds that if you find talented people and equip them with the right skills for the challenge at hand, they will perform at their best. In our experience that often isn’t so. Energy is the X factor that makes it possible to fully ignite talent and skill.

***

You Must Become Fully Engaged

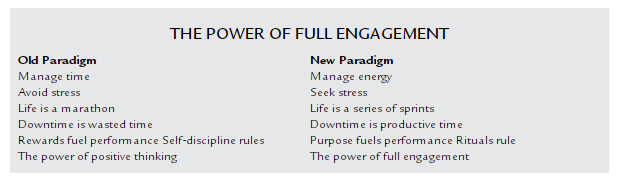

Here are the four key energy management principles that drive performance.

Principle 1: Full engagement requires drawing on four separate but related sources of energy: physical, emotional, mental and spiritual.

Human beings are complex energy systems, and full engagement is not simply one-dimensional. The energy that pulses through us is physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual. All four dynamics are critical, none is sufficient by itself and each profoundly influences the others. To perform at our best, we must skillfully manage each of these interconnected dimensions of energy. Subtract any one from the equation and our capacity to fully ignite our talent and skill is diminished, much the way an engine sputters when one of its cylinders misfires.

Energy is the common denominator in all dimensions of our lives. Physical energy capacity is measured in terms of quantity (low to high) and emotional capacity in quality (negative to positive). These are our most fundamental sources of energy because without sufficient high-octane fuel no mission can be accomplished.

[…]

The importance of full engagement is most vivid in situations where the consequences of disengagement are profound. Imagine for a moment that you are facing open-heart surgery. Which energy quadrant do you want your surgeon to be in? How would you feel if he entered the operating room feeling angry, frustrated and anxious (high negative)? How about overworked, exhausted and depressed (low negative)? What if he was disengaged, laid back and slightly spacey (low positive)? Obviously, you want your surgeon energized, confident and upbeat (high positive).

Imagine that every time you yelled at someone in frustration or did sloppy work on a project or failed to focus your attention fully on the task at hand, you put someone’s life at risk. Very quickly, you would become less negative, reckless and sloppy in the way you manage your energy. We hold ourselves accountable for the ways that we manage our time, and for that matter our money. We must learn to hold ourselves at least equally accountable for how we manage our energy physically, emotionally, mentally and spiritually.

Principle 2: Because energy capacity diminishes both with overuse and with underuse, we must balance energy expenditure with intermittent energy renewal.

We rarely consider how much energy we are spending because we take it for granted that the energy available to us is limitless. … The richest, happiest and most productive lives are characterized by the ability to fully engage in the challenge at hand, but also to disengage periodically and seek renewal. Instead, many of us live our lives as if we are running in an endless marathon, pushing ourselves far beyond healthy levels of exertion. … We, too, must learn to live our own lives as a series of sprints— fully engaging for periods of time, and then fully disengaging and seeking renewal before jumping back into the fray to face whatever challenges confront us.

Principle 3: To build capacity, we must push beyond our normal limits, training in the same systematic way that elite athletes do.

Stress is not the enemy in our lives. Paradoxically, it is the key to growth. In order to build strength in a muscle we must systematically stress it, expending energy beyond normal levels. … We build emotional, mental and spiritual capacity in precisely the same way that we build physical capacity.

Principle 4: Positive energy rituals—highly specific routines for managing energy— are the key to full engagement and sustained high performance.

Change is difficult. We are creatures of habit. Most of what we do is automatic and nonconscious. What we did yesterday is what we are likely to do today. The problem with most efforts at change is that conscious effort can’t be sustained over the long haul. Will and discipline are far more limited resources than most of us realize. If you have to think about something each time you do it, the likelihood is that you won’t keep doing it for very long. The status quo has a magnetic pull on us.

[…]

Look at any part of your life in which you are consistently effective and you will find that certain habits help make that possible. If you eat in a healthy way, it is probably because you have built routines around the food you buy and what you are willing to order at restaurants. If you are fit, it is probably because you have regular days and times for working out. If you are successful in a sales job, you probably have a ritual of mental preparation for calls and ways that you talk to yourself to stay positive in the face of rejection. If you manage others effectively, you likely have a style of giving feedback that leaves people feeling challenged rather than threatened. If you are closely connected to your spouse and your children, you probably have rituals around spending time with them. If you sustain high positive energy despite an extremely demanding job, you almost certainly have predictable ways of insuring that you get intermittent recovery. Creating positive rituals is the most powerful means we have found to effectively manage energy in the service of full engagement.